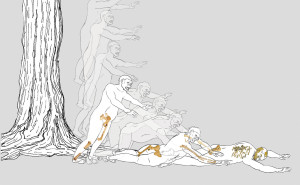

An illustration shows how Lucy might have fallen from a tree, and the broken bones stemming from her fall. — John Kappelman/Nature

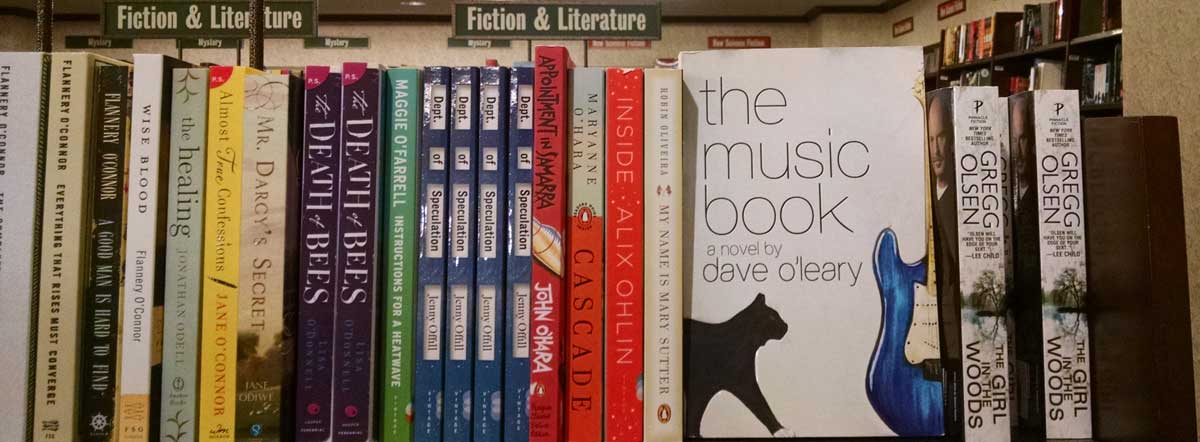

I saw in the news that some scientists think they might have figured out how Lucy died. I couldn’t help but smile. Not because Lucy died, mind you, but rather because she was in Horse Bite. In the opening chapter, I wrote about Lucy, Australopithecus afarensis, evolutionary celebrity, and contrasted her with a possible love while wondering about time and death and multiple lifetimes in the course of one.

Lucy inspired me way back in college. She gave me an idea for a short story that never got finished, but it did bring other things, one of them the start of a novel twenty years after graduation. It was a bit like evolution I suppose. These things take time. For me to actually sit down and write a book, I first had to live a life. I couldn’t yet make it all up. So I played in bands in the Midwest and wrote a few poems and stories along the way. I moved out to Seattle when the bands were all broken up and the girlfriends no more and then spent eight years in Korea not writing a god damned thing. I might have dried up completely if I’d stayed there any longer, but I did eventually come back to Seattle in 2007, and as luck would have it, Lucy came to town two years later. The Lucy.

Australopithecus afarensis. Evolutionary celebrity.

And so I went alone—as I did everything in those days—to see Lucy on a Sunday afternoon, and the writing all came back, or rather it came for the first time really. I did write a lot all those years ago in high school and college, and I tried to impress girls with my poems, but it wasn’t anything. The world is a better place for the fact that I lost all those old notebooks, the same notebooks I once saved when there was smoke in our house in high school and we called the fire department. “Get out of the house now!” they said. We did, but I made sure to grab my notebooks of horrible poetry first.

And well, now they think they know how Lucy died. I imagined it too when writing about her. I didn’t have her fall though. It was nothing violent. There was a contentment in the moment that most likely is there in very few deaths, and I wrote it that way perhaps because it’s something that still frightens me, the idea of how and when it will happen. Love is the same way, and having that now, I never want to lose it, but that is, of course, what makes it so special in the first place. I don’t believe in any god or afterlife, but I like to think—as I imagined in the book—that my bones might someday be on display somewhere for someone millions of years from now to wonder over, to study, and maybe even be inspired by as I was on Lucy’s visit to Seattle.

I’m sorry, Lucy, for the frightful and agonizing death you endured, but yours was not a life lost in vain. You’ve gone from that Ethiopian plain to museums and textbooks to world tours and to an appearance in a novel by a little known writer on the edge of the United States. With a little luck, we’ll hit the best-seller lists someday. The chances are small, almost minuscule, but then so was the fact that you ever made it to Seattle in the first place.

The following is an excerpt from Horse Bite.

Chapter 1

June 28, 2009 2:00 P.M.

It is a simple collection of bones.

They are fossilized and arranged just so to give the recognizable shape of a human skeleton, or more accurately a hominid, Australopithecus Afarensis, Lucy, over 3 million years old and discovered one day in Ethiopia in 1974 as her elbow bone was protruding from the earth as if to say, “Hey, I’m over here.” She was found thus, dug up, preserved, and now thirty-five years later she’s worked her way over to the States where she’s on display at the Pacific Science Center in Seattle.

One can easily skip the awe and say it’s just a few bones, very old bones, yes, but still, only bones, that they look like plastic bits of a model spread out on the floor with some pieces missing, eaten by the dog perhaps, or stepped on and broken and tossed about, or lost behind the sofa or the bed. But they are not model pieces. They are Lucy, 3.2 million years later of her, from the ordinary Ethiopian hill to a Sunday afternoon in Seattle. It’s a miracle that such a fragile thing still exists, that such bones are there in that glass case with enough completeness to be unmistakable even to the untrained eye.

She died of causes unknown all those years ago and fell to the earth. Perhaps it had rained, or perhaps she slipped into a hollow that not long after filled with water or mud, or somehow was lain intentionally by those in her group or tribe in a manner that by chance and coincidence protected so much of her for so long a time. And thus after all the millennia of shifting sands and soil, layers and strata pushing up and down and sideways, and rains and wars and civilizations, there came that day when her elbow was sticking up out of the earth as if using it to nudge someone over, “Hey, quit your crowding.” And on that day of her nudging, there was an anthropologist walking by who, as such things happen, looked over for no reason just at the moment when he would have seen the elbow, when it would have been unmistakable to the trained eye, “Hey, I think that’s an elbow.” The rest of us, those untrained eyes, would have seen a stick, a hill, a sunset, a patch of grass.

But it was an elbow. It was Lucy. And there she is now, well, what’s left of her anyway, which given her age is quite a bit, enough for the imagination to give rise to scenes of Lucy strolling the country side, plucking fruit from a tree, a low branch given her height, and sitting in the shade to enjoy the eating of it while watching the sun settle down behind the hills in the distance. She tapped, I imagine, a rhythm with her right hand fingers on her right thigh, just above the knee, ate with her left hand as the sun sank away. Perhaps she died while eating that fruit, say a mango or a banana, tapping that rhythm, and fell back there by the tree. The rain set in. Her head tilted sideways to the right, eyes closed. The soil loosened, and she slid down the hill to be covered for eons. Until one day when she nudged the earth with her elbow, “Hey, let me up.”

Evelyn said that to me once, back in the last days of my time in Columbus, Ohio, spring 1998. I’d first learned about Lucy in college a few years earlier. It was my last quarter at Ohio State, and I needed another science credit to graduate so I signed up for Anthropology 101. It was a good course, piqued the curiosity, got me thinking about first women, the first woman I slept with, the first woman I lived with, the first woman who loved me, the first woman ever. And then three years later, I mentioned Lucy to Evelyn, the sandy blond coffee shop co-owner, my boss, who had majored in Anthropology. It was an in. I told her of a story I was writing about a man who meets the first woman who matters who of course is named Lucy. She liked the idea. We developed a friendship that hinted at more and then went for it even though she was married. We spent time in the back of the coffee shop together talking at first of Lucy and my story, of Mrs. Dalloway which I’d had in my possession when we first shook hands and said our hellos. That lead to talk of orgasms and the search for their description in literary terms. We spoke of evolution, of our common interests in music, Pearl Jam’s Yield in particular. She put that on once at a party as we ate pineapple and smoked marijuana. We passed the joints and turned up the music, went through that CD three times.

The pineapple ran out somewhere during the second play of the CD so I picked up the acoustic guitar from behind the lamp in the corner and played along with the bass lines. Evelyn and a guy in a Cincinnati Reds cap tapped the rhythms on the coffee/pineapple/marijuana table as a few others danced. One guy passed out on the toilet in the upstairs bathroom, pants down around his ankles. Someone took photos of him of course, but we left him there because the rusty strings of the acoustic mixed with the pineapple residue on my fingers, and the sounds were good. And though the pineapple was gone, the smoke and the music and the rhythm tapping took hours to settle. After the party wound down, I slept on the couch alone, at whose house I do not these days remember, and the music stuck in my dreams with images of Evelyn sucking on a slice of pineapple and taking a hit.

We stayed late in the coffee shop one evening. It closed every day at 3:00 P.M. so after we cleaned up we sat in the back drinking a couple of beers with the other owner and her boyfriend. Then we moved to the front window where there were two love seats. We had Rolling Rocks with limes, which went well with her mango green eyes, and we talked and joked and held hands. The other owner and her man left so we could be alone. Before leaving, the boyfriend had said, “By the time we come back, you should have something to tell.” Evelyn was in the bathroom and hadn’t heard, didn’t know they left to give us a moment, to give me time to seal the deal. She came back with two healthy shots of tequila, Cuervo, and two opened beers. “Have another?” We did the shots and chased with the beers, laughing as each of us dribbled liquid down our chin. We sat back down, faced each other, sipped again.

“Are you really going to do it?” she asked.

“Yes.” We sipped again.

“I’m proud of you.” We clinked bottles.

“And I you,” I said. “You have your own little trip planned too.” We settled a little closer.

“You’ll send some poems, right?” I leaned in and kissed her once, leaned back and had a sip. We wanted each other, but the idea of her marriage was still in the way so we drank and held hands and just kissed a little and drank and drank the beers and the shots and kept getting closer and closer on the love seat as the empty bottles accumulated on the floor. She was eventually laying with her head on my lap giving rise to very sexual thoughts in my head, but we talked only of my leaving as I stroked her hair and she my knee. “How long will it take you?” she asked.

“Oh, about five to seven days.” We both sipped again.

“I’ll miss you.”

The air hung silent with those words. They swirled in my brain.

I’ll miss you.

It was as close to a declaration of love as we could get.

“And I you.”

She returned to tracing the shape of my knee, and I wanted nothing more than to sit and let her do so, but with all the beer consumed, my bladder was calling. I stood up to go to the bathroom. Evelyn looked up at me, smiled, and closed her eyes. We touched hands briefly before I walked to the back of the shop. In the bathroom, I decided that when I went back to her I would give it a try. Marriage in the way or not, I would do it. When I got back though, she was still and seemingly asleep. I touched her hair. She opened her eyes, but before I could fulfill that long awaited desire she leaned up and pushed her head slightly forward, then gave a quick shudder with her shoulders, and then another. I thought perhaps she was going to lean in and kiss me, but she rather leaned to her left, back over the corner of the sofa and threw up in a trash can, a little white plastic thing there for customer convenience. When the sounds subsided, she leaned back full length on the love seat with her feet hanging off the end, and her eyes closed. I wasn’t sure if she’d passed out so I watched her for a little while until the smell of vomit hit me. I blamed the trashcan. With all the force in my being, I blamed the trashcan. I looked at it with anger, and then Evelyn leaned into me with her elbow, softly but with much effort, mango eyes still closed, “…Hey…let me up…I think…I’m gonna be…” She made for the bathroom with her left hand over her mouth. Damn trash can.

For as old as Lucy is, she looks pretty good. She gives a little inspiration. Perhaps then in some far-off time, my fossilized bones will be in a museum somewhere, and in the language of the day they will say, “See this specimen. The interesting thing here is the bent posture with the head down and the position of the hands, left hand extended out, the right hand anchored over the abdomen, clearly indicating that he died while grooving with a musical apparatus known so long ago as an electric bass guitar.”

I can only hope the end is so good, to die, to draw that last breath with bass in hand, to have such contentment in the moment of expiration for this lifetime, and to hope the millions of years afterward, all the subsequent lives, are so kind to me as they have been to Lucy.

A week after the trash can incident, Evelyn and I went to an open mic poetry reading. I read a few, we had a few. We kissed again. No one got sick, but then eight days later, we both left Columbus. I got in the van and drove west to Seattle. She took a solo vacation from her husband. Before going, I saw her off at the airport back in the days when non-passengers could get into the terminal. We didn’t say much. She’d already said it, “I’ll miss you,” and I’d already promised to write and send the finished poems and stories to her. I watched her show her boarding pass and walk down the gangway, turn for one last look. She gave a quick wave and then just stared. We both did for a moment. I breathed three times in and out and imagined she did the same, and then she turned and was soon out of my sight and life.

I walked up to the window by the gate and watched the plane for a good thirty minutes without seeing her in any of the little windows until it backed slowly away from the terminal taking some piece of unknown size from my chest and brain with it. I turned then myself and left and with a mixture of sadness and resolve, I hit I-70 west with Yield cranked. It was a gray St. Patrick’s Day in 1998, and I knew it would rain both in and out of my van.

And this week, I’m here to see Lucy not without a little excitement for the opportunity to look, to observe, to contemplate and remember my talking to Evelyn about the story that never got finished and the relationship that was not consummated. And yes, it is difficult to imagine. All those years. Where does such time go? How often has the sun set in that span of time? How many rhythms have been tapped on how many thighs just above the knee, or on tables? What does such time do to the hair, the eyes, the bones, the music within? Years of my own life go by, and I can hardly remember what it was like to live back there, in the Midwest, in Ohio where Evelyn once lived, where she may still, where, I imagine, she’s still tapping rhythms on tables with tropical fruit and some green. A mere eleven years, but there’s nothing mere about it, indeed another life. 3.2 million? It staggers the mind. Even eleven, just one over a decade, seems a different lifetime, a bygone age.

And in the years since the trash can episode—damn trash can—I still wonder at times what Evelyn might be up to, if she still has that sandy blond hair hanging down her back or sometimes down front around her right shoulder, never the left. And her eyes of course. I wonder about them, mango eyes bright with the knowledge of evolution, eyes that bit her lower lip as she scrubbed counter tops and talked about drinking beer after hours in the shop, eyes that sometimes widened suddenly while listening to poetry and that closed while drinking double shots of tequila, eyes that remained closed after vomiting. I got to know those eyes, the lips too, even though it was all that lay beneath that I really wanted to know. And through the ages I still want to know, long to know them better as I look upon Lucy’s bones there in the glass case. “Where might you be up to?” I mutter to myself.

Lucy does not answer. Evelyn does not answer. But the woman standing next to me certainly does with a look that says she heard my question, a look that replies with the dull surprise of her brown overweight eyes, “Dude, it’s a box of bones. It’s been dead for…for…well, it’s been dead for a long time.” Those eyes roll, and she moves left with her own body, down toward Lucy’s feet, or where the feet should be. And she is right of course, it is nothing now but a box of bones, the flesh that surrounded them so long gone, and yet I have them both, Lucy and Evelyn, on the brain on this Sunday afternoon, both still beautiful after the ages, and both still very much alive.

And so here today I trace my fingers along the bullet point history of Ethiopia. I read about the formation of fossils and the discovery and naming of Lucy, bump into the other people as we look at cultural artifacts and other ancient fossils, the simulated animations of Lucy walking. We look at each other, all of us here on a Sunday afternoon. There is anticipation, even excitement, in the air. We are here to see Lucy, Australopithecus afarensis, evolutionary celebrity.

And we make our way to the back, past the various fossilized skulls and up the ramp to the back room where they only let in a few at a time. I wait. They let a few people in, and I wait. And more people go in, and I wait. And again. And again. And finally I am in. The room is dark. There is a skeletal replica on one side, a full replica on the other, and there in the middle of the room is a glass case with a black frame. It is lit from within. There are a few people standing around it. They are stiff and tentative, one of them a woman with brown overweight eyes.

I approach the case slowly. Eons and ages spanned to get from there to here. And I remember the story, my in, about the first woman who mattered and how I told Evelyn about it, and that she sometimes asked me while wiping down the counter if I’d made any progress on that story. I circle around and come at the case from the head side, looking top-down at the pieces of skull, a jaw bone, some ribs, a femur. It glows. It is mellowing, humbling. Breathing and conversation are hushed, the heart rate slows, the pulse echoes in a way that indicates no difference between 11 and 3.2 million. Lucy and Evelyn, lives, threads, histories with bitten lower lips and mango eyes and beers with limes, and moments, moments that last ages after words have been said. I’ll miss you.

With my right hand, I reach out. The lips are silent, and gently, I tap on the black frame to the rhythm of the mango eyes and the sandy blond hair of ages. It is my in, and I realize, Evelyn, that all these years later, that although I am so close to the Forty you once asked about, I still need an out.